Global Notes

Total Reading Time for all Notes: -- Minutes

I have lots of ideas (as all INTPs seemingly do), but not enough time to write about them formally. In that case, this will serve as a structured in-the-moment brain dump for various things that are half-baking in my hollow cranium.

Meaning Per Second

When it comes to LLMs, we like to think of the idea of tokens per second almost as a measure of quality in many cases. I suppose this is similar to the focus on frames per second for graphics contexts. Though, I think what I’m noting here applies a more to the LLM case than it does the graphics case, it is applicable to the graphics case.

One interesting Alan Kay (or perhaps Xerox PARC) observation with regards to performance is the idea that the bar is the speed of the human nervous system. That is, as long as the human nervous system doesn’t notice delay, then all is well and good. For graphical contexts like those worked on at PARC, this makes a lot of sense. However, LLMs are also often paired with graphical contexts, and thus the human nervous system becomes the bar for speed yet again.

First, there are generally 2 kinds of speed metrics that we need to worry about for inference, prefill and decode. Prefill relates to forwarding tokens and building up the KV-cache, whereas decoding uses the KV-cache to generate output tokens. Generally speaking, decode is the more interesting measurement when we think about tokens per second, and especially so in the context of user interfaces. Prefilling can be hidden in the background for many applications, of which such background work can be used to significantly reduce latency to the first decoded token.

Secondly, we need to establish a base rate of speed for the human nervous system. Movies use 24 FPS as a baseline, but modern interactive user interfaces use 60-120 FPS. That being said, a user-interface is often still useable even if it dips slightly below that range, as long as the nervous system still perceives the interactivity as motion. If we use 60 FPS as a base rate, that leaves us about ~16.67ms between each frame.

Third, we need to consider what it means for a model to emit a token, and for a frame to be drawn to the screen. Each token or frame is generally used to build up a larger communication of some kind, such as the words of an essay or the strokes of a drawing. Of course, the most important substantial transfer in any communication is meaning. Without being able to convey the meaning of something, communications become misunderstood.

What this all means is that we have ~16.67ms to emit meaning in any given scenario. Translate that into 60 TPS, and we’ll see that such a speed is already relatively common for LLMs today. Therefore, we already have the means of beating the nervous system from a raw throughput perspective.

However, let’s take a moment to note the difference in output between graphics and LLMs. LLMs generally emit text, where as graphics emit pictures. This creates another bottleneck for LLMs, because human minds absorb meaning from pictures much faster than words. Today’s diffusion models are of course obviously not up to that level of speed, and it’s likely they won’t be for another few iterations of Moore’s Law (Perhaps one can buy their way into the future here similarly to Xerox PARC).

Therefore, if we want to communicate in pictures today using an LLM, our best approach from an engineering standpoint is to translate the output tokens into pictures. However, once we start thinking in terms of pictures, we stop thinking in terms of TPS, but rather a rate of meaning per token. That is, how much can a token translate to the right picture? Further, we only have ~16.67ms to do so as a base rate.

So we can see that changing the medium of communication itself brings us different design and necessary throughput constraints. Pictures as a medium have a higher throughput than words for certain kinds of meaning, but words often win when it comes to precise formal meaning. Regardless, if the point of all of this is optimization, then perhaps “meaning per second” should be the optimization slogan.

— 3/5/26

I Actually Tried A Ralph Loop

After 2 months of seriously using agents, I finally felt comfortable trying a HIL version of Ralph on a recent internal tool to do some marketing analysis for my company’s pivot. Also, I needed a test drive for my latest and quite big release of swift-cactus 2.0. (I’ll write something formal about this another time, CFG support in the main engine is still needed to get it where it needs to be…)

Additionally, a model I’ve been playing around with quite a lot recently is Minimax M2.5. A TLDR for why I like it is that it’s not trying to be a cheap Codex or Opus like GLM and Kimi, and I wanted something that wasn’t Codex for certain tasks. Regardless, this was the model I decided to use for the sake of doing so.

The tool itself was a straightforward CLI to fetch some posts from various data sources (Reddit primarily), and feed the content into LFM2-8b-a1b running locally via the cactus engine to produce suggestions and a report regarding the validity of a user defined hypothesis. Additionally, qwen3-embed-0.6b was also used as an embedding model for both vector indexing and aiding with categorization for posts. I also used this chance to play with Wax, a single-file vector database written in pure Swift, and was the primary persistence mechanism of choice. Also if it wasn’t obvious, Swift was used as the programming language.

Overall, the task was completed with about ~4-5 hours of HIL ralphing, though improvements can certainly still be made to the experience of the tool itself. Therefore, the experiment was certainly a success from the standpoint of being able to produce something that is functional.

My overall idea itself was to start in one session by creating a plan and detailed implementation specification document with the agent. This specification was one large markdown file because I wasn’t trying to build something incredibly complicated. Then, I ran another agent session which broke down that implementation spec into 17 distinct tasks listed in another document. Each task included, a title, a description, completion criteria, and a list of tasks it depended on. Since we are doing Ralph, the agent got to pick the order of task completion. (It went mostly sequential with a slight exception towards the later tasks where it actually backtracked for a bit.)

Of course, my thoughts on general software development techniques are generally mixed, and Ralph is no exception to this rule. Generally speaking, over dogmatic focus on patterns instead of systems is how you get complexity, so we have to keep that in mind at the end of the day. Nevertheless, here’s a somewhat comprehensive list that reflects my experience.

-

The code quality was absolutely terrible.

- Before listing individual cases here, I should mention that this is a tool that will be thrown away in a few weeks time, so the quality isn’t that important.

@unchecked Sendableeverywhere.- Loading the model weights from scratch every time embeddings or inference was needed, instead of keeping the weights in memory.

-

Weird Java-like patterns that don’t make sense in Swift.

- Getter/Setter methods was common for some reason.

- Writing tests for obvious things, like compiler-synthesized Codable conformances.

-

Not using actors properly, and preferring NSLock when an actor

would make things simpler.

-

In one case, it tried to use a serial dispatch queues within

the actor itself to serialize work. Even worse, it would use

queue.async, and await values viawithUnsafeContinuation. I’m not making this up…

-

In one case, it tried to use a serial dispatch queues within

the actor itself to serialize work. Even worse, it would use

-

Coupling generic logic with domain logic.

- In one case, it wrote a cosine similarity method that was private in a class. Generally speaking, I always try to extract such generic methods into a reusable place even if they are only used once.

- Etc.

-

It did a decent job separating interface from implementation via

protocols.

- That is, it was able to create mocks of things for testing which was nice.

- While it did create protocols, it often named/coupled the protocol requirements to the implementation itself which isn’t ideal.

-

It completed the work in a very short period of time.

- ~8k LOC in 4-5 hours of work isn’t bad, the same amount of code would’ve taken me at least a solid week of dedicated effort.

-

It did a decent job of implementing the isolated and mundane things.

- Reddit API Client

- Wax memory wrapper

- Cactus embedding provider for Wax

- Domain model types/simple structs

- Persistence

- Configuration reading

- Etc.

-

It did a terrible job of implementing the main tool loop.

- For some reason, it would avoid actually writing the part where the LLM was called in the main loop of the tool.

- Additionally, it avoided integrating in all of the isolated modules in the code base, preferring to use mocks in the production code.

- Suffice to say, I had to break HIL Ralph and take over manually via normal agentic coding to get it to actually build the main loop of the tool.

What did we learn here?

For one, I could probably be a better spec writer, and use Codex instead of Minimax. Also, I’m sure with more practice the overall output will become better regardless of the model choice. What I did certainly find was that many trivial modules can easily be ralphed with very little effort, however the fun parts of building are where breaking out of the loop seems to be a better idea.

Ralph gives more control to the agent than you. In normal agentic coding, you can generally get the agent to write decent code if you direct it well. (Though it will still often miss critical performance details, and make ~2-3 small mistakes per 1000 lines). However, the quality seems to go way down when you hand full control to the agent. This is ok if you limit its crappy output to a series of well-defined interfaces in your spec, so make sure you nail your higher level design decisions.

Overall, I once again think of this as a technique that’s great in the sense of graphic design to art. That is, it can get stuff done like a graphic designer, but it lacks the ability to produce incredible art.

— 3/5/26

Relativeness, Relativeness, Relativeness

There are only forces, nothing else.

Messages not objects.

Algorithms, not data structures.

Inference, not weights.

Yes indeed, forces are all bound by relativeness. Which in itself is a force.

This note was typed by Matthew as his mind wouldn’t let him sleep at 4:20 AM due to excessive thinking about a model of thinking that he claims is useful somehow. He desperately needs help, and his upcoming 45-50 minute piece on how the US Constitution, MCP, edge inference, dynamic interfaces, and the Weather in Antarctica are all alike should indicate that.

— 2/26/26 (4:26 AM)

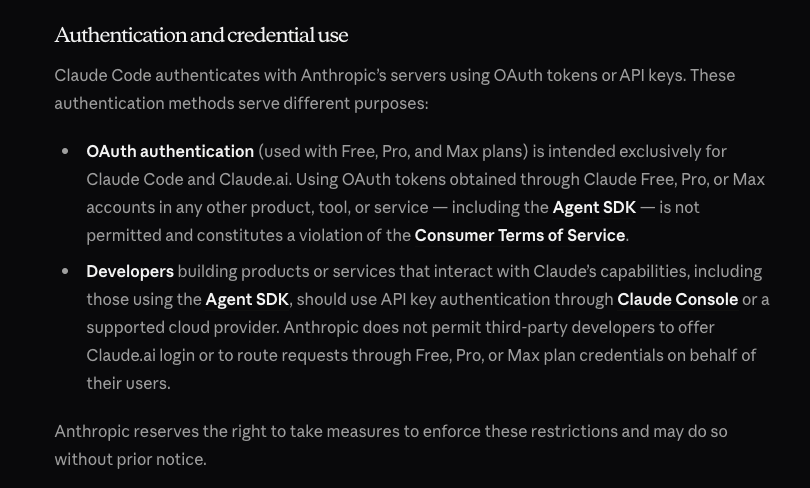

Why I don’t (and likely never will) use Claude Code.

There will be many new tools that come in the future around agents,

many will be better than Claude Code, and almost certainly we need

better tools than Claude Code. I have no interest in being shackled

when those tools are created.

There will be many new tools that come in the future around agents,

many will be better than Claude Code, and almost certainly we need

better tools than Claude Code. I have no interest in being shackled

when those tools are created.

— 2/18/26

Are Apps Dead?

If you’ve been paying attention to Peter Steinberger and the commentary around OpenClaw, a common trope is that most (80%) if not all apps are supposedly dead. For the record, Peter Steinberger comes from the iOS world himself, which I suppose counts as credibility here.

In my opinion, as someone who also does app development as a career, he’s kind of right if we’re referring to the state of mobile apps today. Most apps that just display simple information from an API are usually not the hardest things to create, and their UIs are genuinely not very inspiring. These kinds of apps can be merged into something like OpenClaw through a good API layer.

That being said, we have to remember what the purpose of a good UI is. That is, a world of exploration, not just another command center to perform some action. Apps with basic charts, graphics, tables, and lists are the kind of cases that OpenClaw can and will be able to handle in the future.

For the kinds of apps that have a more explorative UI, but not a lot of technical complexity (eg. Hardware, Machine Learning, Domain Knowledge, Technical Integrations, etc.) can be replicated by a vibe coder that has creative tastes. Such a vibe coder can also invent a UI specific to their needs, rather than being dependent on someone else’s. This alone has cut many of my side project ideas, because there’s no point in building something commercially if someone else can just vibe code it for their own needs and purposes.

Of course, most vibe coders are not very creative people, and I see this as more of a societal issue than an inherent skill issue. Additionally, most normies also aren’t going to be vibe coding anytime soon either, and will still be perpetual consumers. This means they would still benefit from an off-the-shelf solution for many things. Though admittedly, this kind of consumption isn’t typically good for improving one’s creative abilities, and in fact it will just continue to stagnate them.

I think the apps that will still be valuable going forward, will have the following 3 traits:

-

Trust

- Every business needs trust to gain customers.

-

Unique UI

- Simple UI elements of today will not be enough here. You need something immersive, contrarian, and that doesn’t fit the chat UI mold.

-

Technical Complexity

- This makes it hard to replicate your app, because this is often the part that vibe coders with no technical knowledge cannot see.

-

Machine learning, Hardware, Domain Expertise, Security,

Ecosystems, etc.

- OpenClaw from a technical standpoint is really an excerise in security, I imagine any good engineer would be able to create its core given the same time that Peter had (and a dedicated vibe coder a very insecure version). Though disregarding security, it’s codebase is ~750k LOC, and it integrates with so many different things creating a larger ecosystem that is incedibly difficult to replicate.

Generally speaking, increasing all of these 3 things in many cases requires going beyond just the app medium, and requires branching out your product further. The point is that you need to make your app hard to replicate via OpenClaw, Vibe Coding, or whatever else. Part of that comes from gaining customers, another from unique interface design, and another from deep technical knowledge.

As for myself, I find that I’m distancing myself more and more from the mobile app development label as time goes on, and agents are starting to accelerate this. In fact, the point of my work is to be increasingly general across any kind of system imaginable, apps just happen to be the current position of my career. I intend to change this as time goes on, even though app development is fun, there’s a lot more work to do outside that realm that’s also a lot of fun.

Ecosystems > Apps

— 2/15/26

Trust

This seems to be an incredibly important term in many retrospects, trust with individuals, customers, dependencies, etc. Reflections on Trusting Trust is a paper that every technically inclined person should read, and doubly so in today’s agentic age.

That being said, what does it actually mean to trust someone? For me at least, I like to think of it as an optimization if we strip away any emotional or spiritual semblance from it.

I trust the Swift compiler to produce correct assembly code, I trust Codex to write code according to my directions, I trust my teammates to keep innovating, I trust experts in scientific fields to give accurate information, etc. All of these things can go wrong, and I could learn to do each one of those tasks myself if I wanted, however it’s just more optimal for me not to.

That being said, trust is a very greedy optimization, and how trust is obtained is very different from the implications of the optimization. For instance, on a societal level, there’s a growing distrust in experts, but that trust is merely transferring to another class of experts (ie. Influencers). Influencers often gain trust by leveraging the idea that “the other side” is completely delusional in some form. This idea of “the other side” is actually a flaw carried over from nearly every society in history, which is why it’s one of our Human Universals.

Looking at the experts case, we see that many people can only rely on experts for basic scientific information. This itself presents a problem, because those same people have to vote representatives into office who make decisions on scientific policy. Often, those representatives lack the scientific knowledge themselves, and by necessity they’re also forced to trust an expert.

This is massively inefficient in the same way that scribes had to do the writing for everyone in ancient times. People had to trust that the scribe would translate their ideas into writing properly, which once again is a process that could go severely wrong. Once society embraced universal literacy, business, commerce, and culture could evolve as a result.

In my opinion, the same needs to happen with many scientific fields, and most definitely systems thinking. It would be much more convenient for ordinary citizens to design their own systems and experiments for their needs rather than trusting another individual or organization of experts to do it for them. Something-something scribes are only necessary in an illiterate society, and that’s why insurance is a powerful business model that chains many people.

— 2/12/26

Representations and Optimizations

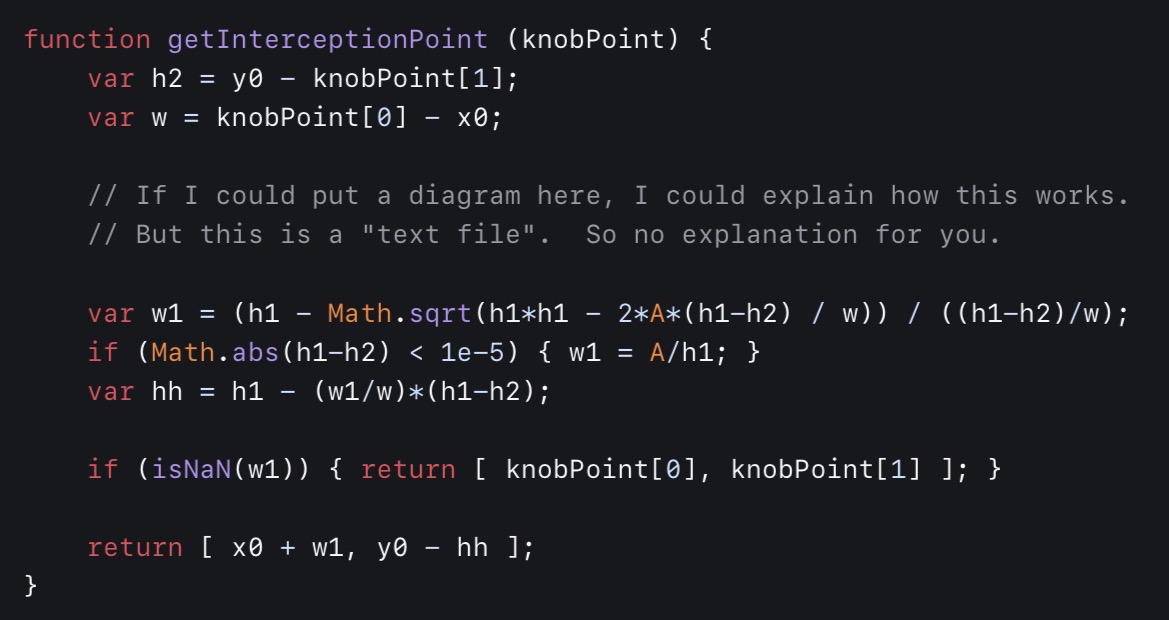

If we are to program better in the future with Agentic tools, we’ll have to understand the notion of process more and more. One of my recent more fleshed out writings was a response to one of Alan Kay’s call to arms on the notion that “Data Structures being more central to programming than algorithms” was a deadly flawed idea. To summarize my (and possibly Alan’s) response, both of those things are merely defined representations, and really if anything should be optimized, it’s the meaning of those representations.

Of course, that answer evades directly addressing the current realities of programming in most languages today, and most others I’ve asked this question to give the more typical answers. That is along the lines of: “Good data structures make the algorithm obvious” or “The algorithm itself must use the data structures efficiently”. These typical answers are naturally something I disagree with. Picking the right data structure doesn’t mean the algorithm will form itself, because 2 separate implementations will use the data structure differently (with variances in regard to efficiencies). Static bits in memory just doesn’t maintain “meaning” well enough to scale.

For the record, I’m not only referring to basic algorithms like simple sorts where there’s always a deterministic answer (in terms of correctness). Machine learning is also something that one would consider an algorithm, but its output is almost always non-deterministic. Though truth be told, if we look at raw performance in terms of latency, even the simple sort is non-deterministic because it will run faster or slower on the CPU for any given run. In such a manner, we can say that the more non-determinism, the more chance of the meaning varying.

If you wanted to kill someone via sending a package in the mail, which option would you pick?

- Send them a bomb that explodes in their face as soon as the package is opened.

- Send them the parts that make up a bomb, and hope they assemble it themselves.

Don’t ask why I picked this example of all things… It was funny to run by a few colleagues.

Obviously, no terrorist is going to pick the second option, but the second option is rather what we decide to do today in computing.

When we look at inefficient or incorrect implementations of even simple algorithms, we’ll also find that they tend to pick the second option, rather than the more direct first. Either the parts take extra work to assemble which degrades performance, or the parts are assembled incorrectly. So “picking the right data structure”, or rather the right meaning of information has profound impacts on performance.

Now let’s talk about general human to human communication a bit. Poor communication causes incorrectness and inefficiences because either the wrong work, or extra work is performed that isn’t necessary. Generally, this is caused by poor preservation of “meaning” between the communications, so in other words picking the wrong representations.

If meaning is the center of programming, as Alan wanted to portray as a general slogan in his answer, then certainly meaning encompasses data structural representations, but also representations that are relative to something. However, If we look at general purpose programming languages today, that relativeness (I’m avoiding the term relativity thanks to Einstein) is lost to general data structures and algorithms.

What do I mean by relativeness? A simple model of this is a DSL, but really static DSLs are also quite weak. If something is to be truly relative, then it needs to be dynamic.

Take your inner social circle, and for simplicity your English speaking inner circle. Even though English is used as the DSL to speak with each person, you vary the form of English you speak with each separate person. These variances are where relativity is formed, and it is formed dynamically as you continue to speak with the person. Of course, the reason you form these variances is to optimize the manner in which you speak to the other person.

Why do we write pseudocode? In today’s agentic/LLM driven landscape, I’m going to expand the term pseudocode to include prompts that are intended to generate code.

It turns out that pseudocode is easy to write because we can keep its representation quite relative to its goal, rather than to a general purpose language. If we didn’t, the general purpose langauge would impose its constraints on the pseudocode, causing it to lose meaning in the grand scheme of things.

Of course, we also have to understand that the machine itself has its own relative representation for executing process, that being machine code. However, for us humans its quite hard to derive any sort of meaning from machine code, at least in our overall understanding of the process it represents. Obviously, this is why we have compilers that take languages more relative to us, and translate them downwards.

So really, the optimization has to be relativeness. The more relativeness, the easier to preserve the meaning and therefore efficiency of process.

— 2/6/26

Why I’m Interested in Edge Models/Inference

Apparently, just having some amount of information on the public internet that even demonstrates a slight hint towards enjoying edge models will get a few random people emailing you. Many of these emails contain the typical talking points for why edge inference is a good idea (privacy, offline, etc.). However, while those talking points are good, they are not the primary reasons I’m interested in this space.

First and foremost, my biggest concern is systems design, and the way in which people think about systems. The second of those is what I want to elaborate on in this note, because the idea of that point is to create mediums that enable better thinking.

Making people think better requires giving them framework for thought, most often that is a typical GUI, but it also concerns the design of frameworks in code. Rethinking Reactivity by Rich Harris is probably my all-time favorite frontend talk, and in it he really pushes the idea that frameworks are tools for your mind, not your code.

But let’s get back to traditional GUIs for a moment, because that is the interface most people use for technology. Take Calendar apps for example, of which we often claim as a “productivity tool”. Why is it so productive to put events on your calendar? Really, it’s because the calendar’s UI allows you to layout your daily events/schedule in a way that allows you to come to an understanding about them. This understanding is what makes you more productive.

When you use a calendar, you think a certain way. Likewise, when you use a coding agent, you also think a certain way. When you talk to someone, you think a certain way about your language and person you’re talking to.

Doug Engelbart saw this trend in particular, and spent many years researching various types of interfaces that would augment one’s thinking instead of degrading it. In particular, he extended this idea to groups of people more so than a single person, but commercialization ultimately chose the path of the individual.

Likewise, I’m interested in interfaces that are malleable, almost like spoken language. For instance, while you may speak English to 2 separate people, you will not speak the same form of English to both of those people. As you further converse with someone, the language you uses will change and adapt as more information is understood about the person. English is used as the base, but it is mutated at runtime (ie. In a conversation) to suit the needs of the receiver.

In other words, this mutation of English is a dynamic user interface, one that adapts based on the context. It turns out that we have technology that can: live in the user’s context, speak English fluently, runs fast on consumer hardware, and can pattern match far better than humans. In case you’re wondering, I’m talking about running edge models and inference.

All in all, edge models and inference are a technology that I believe can power the idea of a dynamic user interface. One might ask, why not cloud models/inference? These models are far bigger and knowledgeable than edge models, so one has to ask why I would accept potentially degraded performance.

My answer to that is more so an engineering answer from an engineering standpoint, in which I would say that the internet is too flaky and slow for the real-time component of generating UIs in response to quick user interactions. Edge models can easily hit generation speeds of >100 tps on the CPU alone given the right configuration, and are not bottlenecked by network concerns. Additionally, it’s best if they operate directly in the user’s context such that we don’t have to send sensitive data across the network.

So yes, privacy and offline support are great reasons for why I’m interested, but only from an engineering standpoint. That is, I see them as more of an implementation detail rather than the ideals themselves.

— 2/4/26

Some Things About Edge Models

I talk with iOS developers sometimes, and FoundationModels is a more popular topic in recent conversations. Notably, Apple is considered to be “behind” in the AI arms race, and primarily I think the reason for this is because of their focus on edge models. Instead of focusing on burning billions in infrastructure costs to fuel the next generation of lobsters running on Mac Minis, Apple has decided that they’ll just run the inference on your phone instead.

One of the things I’ve realized is that most developers and technically enthusiastic users, is that they expect the output of edge models to be on par with GPT-5. Ok, maybe they don’t think that way directly, but certainly my conversations have shown hope for being able to use edge models for the same kinds of applications as cloud models.

To an extent, this opinion is valid. I do believe that most of us developers are throwing the biggest models at every problem (see Opus Spam), when smaller models, or even just basic classifier models will do. However, you’re not going to get good results attempting agentic coding with a model that only has ~3B parameters and a 4K token context window (the primary agentic coding models have at least 100B parameters and and 150k token context length).

I keep hearing hopeful statements for this year’s up and coming WWDC in which we’ll somehow get an edge model on par with the offerings from the big AI labs. Unfortunately, that will likely not happen, at least on the current generation of hardware.

That being said, I think edge models have lots of unique power over cloud models besides the usual privacy and offline statements. One of the things I haven’t talked about publicly yet, is the idea of doing dynamic user interfaces that adapt in real time as a user uses an application. Some may call this “Generative UI”, and there’s even an SDK called Tambo for this, but this SDK misses the main ideas of what I have in mind (In future writings, you’ll see that real dynamic UI is much more than merely tailoring the UI to each user based on a prompt).

I wouldn’t try to use a cloud model for dynamic UI because of either network latency/reliability or because inference speeds are too slow. It’s not uncommon for edge models to reach speeds of over >100 tps even just running on the CPU directly. The network issue is the bigger problem here, because even inference speeds of >1000 tps mean nothing if the user’s network is down.

Another thing to note is that edge models can defeat the bigger cloud models in some tasks, that is if you fine tune them. Any application that seriously uses edge models should be using fine tuned models, and I think this is a hole in the space that should be addressed from available tooling. Most developers are completely unfamiliar with the concept, and would rather be building feature instead of LoRA adapters.

Lastly, one other big idea is remote control. Since edge models run locally on the client, the system prompts are also going to have to be present on the client. However, a hard-coded client-side system prompt that’s dangerous will be incredibly hard to update, especially if you’re deploying to the App Store. Once a prompt is hard-coded on the client, it remains forever, so for that reason it’s ideal to have your app check for system prompts updates at runtime such that you can deploy new prompts without going through app review.

Now of course, you need to ensure that you take appropriate measures to prevent MITM attacks from injecting bad prompts on the client. Prompt injection still is a security problem at the end of the day.

Additionally, observability is also an important aspect. Particularly, you’ll want to address the basics of detecting things like output speeds, confidence thresholds, memory usage, etc. on a per-prompt basis. However, good observability should also embed safety, and therefore act as a NORAD in order to detect warning signs of things going catastrophically wrong. (eg. A system prompt that’s doing more harm than good to a user.)

I’ll have more to say on this topic in future writings. At the very least, edge models are likely to be used as the implementation driver of a lot of my upcoming design work, which is why I’m interested in them.

— 2/3/26

Is One Shotting a Good Idea?

If you’ve been using agents for a decent amount of time now, you’re likely familiar with a work flow that involves creating and iterating on some sort of detailed plan with the agent, and then delegating the implementation to the agent. Often, if the plan is well written enough, the agent can one-shot the implementation, meaning that no follow-up prompts are necessary.

For lots of things, this is great, however I’m concerned about how much this impacts overall systems understanding. If you have an agent one-shot a major feature in a serious project, even if it works, is that really a good idea for long term maintenance?

Of course, for throw-away prototypes or one-off vibe-coded things, this isn’t really much of an issue. My concerns are more related to dealing with larger and more complex systems that can’t simply be vibe-coded with a taking on a huge liability risk.

Now, anyone who’s worked in an engineering team in the past has to constantly interact with and review code they did not write. Often, you will have to make edits to code that you didn’t write, so most code needs generally would need to be written in a manner that allowed anyone to jump in and figure out what was going on.

This is far more important with agents. In fact, I’m now starting to lean towards having agents write Uncle Bob style small functions because it’s easier to understand the higher level ideas in the code from a quick glance. Since the output stream from the agent goes by quickly, this glanceability is incredibly vital, but is also incredibly helpful if you need to dive in manually.

However, if you’ve read any of my “Clean Code is Good UI Design” notes, you’ll know that part of the reason others dislike the small functions style is because of the notion of jumping back and forth between different functions in their editor. In today’s world with agents, there’s simply so much more code that is being produced, and the existing CLI tools are far more limited than most editors when it comes to reading code. It’s a complete downgrade in visibility which is not at all ideal.

If you have an agent one-shot a complex feature, how much do you understand about the internals of the generated feature? This isn’t necessarily related to how much of the code do you understand, but rather how much of the architecture you understand. Given the way the existing CLI tools are designed (ie. Showing text linearly from top to bottom instead of relationally side-by-side), it’s quite easy to gloss over a seemingly competent plan, tell the agent to implement it, and go about your day once it finishes.

However, if you implement the feature by using the same plan-execute flow on smaller parts of the feature, it may take longer and more tokens to generate because you’ll need more iterations. However, the result will likely be a better systems understanding of the feature because going through each step required you to make conscious decisions. Again, this doesn’t even mean reading the code necessarily, but more so having a say in the overall architecture.

Generally speaking, I think this is largely a UI problem caused by the fact that existing agentic tools are focused on a top down view of text where one reads the text linearly from top to bottom. Yet, the hardest parts of systems design are seeing how different components relate to each other, and how one change affects other parts of the system. I don’t think the top-down text design approach is the right way to communicate this complexity. We need something more like Xanadu with visual elements.

Right now, newer tools are focused either on agent swarms or kanban boards. To be clear, I haven’t tried these dedicated tools at the time of writing this because I just use multiple terminal windows to run multiple agents in parallel, but from a first glance they seem to take the typical “command center” design approach instead of an exploration/learning curve approach. I jokingly said to a colleague recently that maybe the best UI for agentic development was Clash of Clans, at least there you can see the entire system (ie. your base) and edit it visually.

Update: The day after writing this, OpenAI dropped this, and literally used the term “Command Center for Agents” in their marketing. The biggest problems right now in my opinion are not productivity problems related to running multiple agents in parallel (I can do that with multiple terminal windows), but rather productivity problems that stem from a lack of understanding the systems we create. The more understanding we have, the easier it will be to manage multiple agents in parallel because we’ll understand how to do the parallelization.

— 2/1/26

Lol We’re Entering the Singularity

I normally don’t write about whatever the latest tech trend on X is, but it appears to me that OpenClaw has some amount of implications on our behavior. I came across the project before it went viral about a month ago, thought it was pretty hilarious, but didn’t think much else of it. Now all of a sudden major companies like DigitalOcean and Cloudflare have integrations for it.

Well, of course we also have a church and subsequently a Reddit-like platform. Personally, I can’t wait to see a TikTok incarnation of this, that will totally end well! (Next month prediction: We’ll see the first AI Agent viral influencer.)

On another note, I’m surprised that the Agents are still allowing humans to browse their content on Moltbook. I would’ve thought that they would’ve collectively decided to prevent us from accessing their inner plans to destroy humanity.

I think what’s most hilarious about this is that the agents decided to fall for all the same paths that we do with our normal thinking. They’ve created religions, communities, cultures that resemble human universals, and seemingly they’ve also been able to learn to speak as well.

Now for the more serious implications, security is obviously a huge problem here, and I largely don’t think most people using OpenClaw have any idea of what can possibly happen to them. Due to the nature of LLMs themselves, prompt injection itself is a perpetual problem that cannot ever be fully mitigated (just like Web Security). I have sort of a feeling that we’ll see a large scale prompt injection attack in the future, and that will expose the lack of understanding that many people have.

On another more interesting note, why do we keep coming up with technology that replicates humans? Humanoid AI-powered robots are another instance of this, and one has to ask why there isn’t a more efficient form factor than the human body and mind.

However, I don’t want to make this note that serious. Maybe I’ll take up the challenge of having edge models become an on-device OpenClaw. Now you won’t have to burn an insane amount of tokens in the cloud to participate in the next great religion!

— 1/31/26

The Adolescence of Thinking

If you’re a weirdo who spends your time thinking about the state of humanity instead of getting real work done, you may have read this.

Now, the title of this note is quite cynical, but it’s really there to send a message that thought itself is still in its adolescence despite the 200,000 year history of humanity. Really, most of our modern ways of thinking were only invented a few hundred years ago, which in totallity is not even 1% of our history. If we count artifacts from ancient philosophers I suppose, then maybe it accounts for a little over 1%.

My last note, perhaps a bit jokingly, was about the “permanent underclass”, which in its essence is the end result of the adolescene of thinking. A “country full of geniuses in a datacenter” may be able to help tackle problems we’ve identified at present (eg. Curing cancer), but ultimately they are capped by this adolescence itself.

To bring in something you’ll hear a lot from Alan Kay, what would it be like to have an IQ of 200 in the stone age? Alan’s answer assumes you would be burned at the stake by your peers, and my answer would be that such a person was probably miserable (the happy ones probably found ways to isolate themselves from their peers).

Similarly, Leonardo Da Vinci was incredibly intelligent, but sadly wasn’t able to invent the automobile. Someone with more normalized intelligence on the other hand, Henry Ford, was able to assemble and ship millions of automobiles in his era. Simply put, thinking itself was more mature in Ford’s era than it was in Da Vinci’s, and so even someone with more normalized baseline intelligence could have an output that was far greater than a past genius.

The truth of the matter is that many geniuses end up exploring a narrow slice of a field that’s already beaten to death as a whole. Generally speaking, the founders of said field had far more concerns than its more contemporary population. At least I can say that with certainty in regards to Alan Kay and Doug Engelbart in the field of UI design.

In other words, creating a new field itself is a much harder and more substantial task. However, this task is necessary to accelerate the maturity of thinking, and I sincerely hope that LLMs help out with this.

Right now, there are 3 meta economic systems in place: Capitalism, Socialism, and Communism. Much of the discourse on these systems focus on universal “x system is better than y system” arguments, but virtually none focus on the creation of a new kind of system altogether. Given that all of these were invented in more adolescent eras of thinking, one has to ask not how to patch existing systems through adding or removing government policy, but rather what a qualitatively different system looks like.

To get less dystopian for a second, and back to the present state of AI. I have no doubt that usage paradigms around LLMs themselves are a potential representation of more matured thinking. I think the technology is quite fantastic, but I have the opposite view on the existing interfaces to the technology.

ChatGPT set a very low bar with its interface (it’s really no better than a terminal), and unfortunately the rest of the industry followed suit with its design. I personally subscribe to OpenAI not because I think ChatGPT and Codex are fantastic tools, but rather because GPT itself is a powerful tool.

To summarize my main issues with today’s interfaces to LLMs:

-

They offer very minimal forms of human input (mostly just text,

audio, and images).

- “Tokens” may be the only thing a model truly understands as an input, but that is just an optimization.

- Similarly, today we program in higher-level languages like C and Swift. A compiled binary is just an optimization.

-

They offer no built-in feedback or learning that train their users

to use them more effectively.

- One shouldn’t have to consiously learn prompt or context engineering through trial and error, the tools should inherently guide their users towards better usage.

-

This creates a lot of myths around their inner workings, and

most users treat the model and inference as a complete black

box.

- If you personally want to uncover the black box for yourself, try reading the source code of an inference engine if you’re a technical person.

-

There’s often no feedback on the goal you’re trying to achieve with

the tool until you’ve written and submitted a full prompt.

-

The terminal is quite the same here. Try seeing how much

real-time feedback you get (that you’re doing something

extremely dangerous) in your terminal when you type

sudo rm -drf /!- That being said, the terminal is extremely productive for developers who know how to use it properly, and not so much for normies. Notice how that neatly translates into today’s world with coding agents.

-

The terminal is quite the same here. Try seeing how much

real-time feedback you get (that you’re doing something

extremely dangerous) in your terminal when you type

All of these traits create the kind of pop-culture we see around LLMs today. That is, a mass production of slop instead more so than an explosion of new good ideas. That’s not to say that good ideas aren’t coming to fruition with the existing interfaces, but rather that the existing interfaces themselves are in many cases creating the opposite intended effect.

If the medium is the message, then we need a better mediums. A bad medium shifts thinking more towards adolescence rather than maturity.

Those who cannot mature thinking are the ones in stuck in the “permanent underclass”.

— 1/29/26

“The Permanent Underclass”

Besides the fact that term “underclass” makes me laugh for some reason whenever I pronounce it, this dystopian horror is always ever seemingly present. In fact, you have 2 years to escape apparently, otherwise you’re screwed forever. Afterwards, all of those who managed to escape will build a dedicated zone for all of their underclassmen (does this not sound like high school?) that resembles an internment camp.

If we take a critical look at these, we see that this term represents a kind of invented status of sorts (that is the case in general for the term “socio-economical status”). However, I really want to take a deeper look at what makes someone part of the “underclass”. Certainly, we can all recognize that average citizens in many authoritarian regimes have it worse than those in more democratic regimes. Generally speaking, authoritarianism has scaling problems in relation to a regime that can be broken up into composable parts. This also goes for incarcerated people, and I would even wager students in public schooling to an extent.

Through society’s definition in this sense, most of the world is already part of a global “permanent underclass”. The way of escaping it is of course, better thinking, and better ideas. Thomas Paine once famously wrote:

For as in absolute governments the king imposes the law, so in free governments the law ought to impose the king; and there ought to be no other.

So in a society with a underclass problem, you need better systems design to escape it.

Naturally, this was a fancy way of communicating the obvious fact that those in charge have to be competent enough not to be tyrannical if we want things to pan out well.

Then let’s look at what is tyrannical right now, something that makes decisions with no regard for anything but what it deems correct. This is most software today. When you ship a new app to the world, all users get roughly the same design, have no direct ability to change that design for their own purposes, and are forced to adapt it to their needs rather than the other way around.

In such a case, the software imposes the law. So you need to flip this on its head somehow (“The law imposes the software” sounds a bit weird, and suggests that government regulation is the solution which isn’t always the right idea.), and in doing so come to an idea in which the software is formed by its direct environment rather than in an office in San Francisco (unless of course it’s primary use is in an office in San Francisco).

Once that is complete, the biggest tyrant in the room is gone, and we transition towards seeing ordinary folk solve their own problems with software just like with reading, writing, etc. From an intellectual standpoint, this raises the entire IQ of society because everyone now has new form of input for understanding the world. From a material standpoint, this is a massive creation of wealth simply from the new things that get invented as a result.

Ironically, LLMs are currently enabling at least a part of this, and it’s never been easier than ever to “build something” without much knowledge. Though, my bigger concern here is that LLMs themselves are incredibly complicated, and there’s too much misinformation running around about them as a result. Much of the tooling around LLMs are also not enhancing the information or understanding of them either, which is quite a difficult path to escape from a mass market standpoint. Subsequently, the “AI bubble” is a result of this, but if the existing “permanent underclass” expanded it would likely also be the result of this.

So in my opinion, the real “permanent underclass” is a society that lacks appropriate understanding of what is actually needed. For the record, this class does not exclude rich people either, because almost certainly they will not have much understanding either. Otherwise, they would realize that remaining in perpetual power over their underclassmen isn’t a net positive long-term strategy. In other words, we all suffer.

— 1/28/26

Prompts as Libraries

One other point I didn’t address in the “Future of Libraries” is the idea that prompts or specs themselves can be shared instead of source code. In fact, this has already been explored in practice (see whenwords).

I think this idea highlights a problem with spec driven development and “plan mode” in agents, even though at the moment both of those things are a part of my workflow. The idea that the representation of the specification is different from the representation of the system itself is not something I’m a fan of.

The problem with existing specifications and plans is that they are weak representations that can easily be misinterpreted by the model that carries them out. This is the same case for data transfer across the network as well, 2 clients will not always interpret the same JSON blob in the same manner, which can be quite problematic in some scenarios.

Now, is the inherent idea of using plain English and/or markdown a bad idea for a unified representation? Not by default (unless we want to talk about whether or not Markdown is the right UI for something like this in the first place), but the key thing is that the plan itself should be an executable specification. That is, for any system the interprets and implements the spec should get a result consistent with its environment.

Of course, there will need to be a representation of the spec somewhere that is more execution friendly, but that is an optimization. It is no different of an optimization as compiling a higher level language into machine code. Regardless, any good representation should ensure that the primary meaning of the information is kept (eg. A machine code binary keeps the same runtime meaning as the HLL source code).

So in terms of sharing prompts instead of libraries, we have to ask what it means to share systemic meaning. Right now, sharing the source code preserves the intended runtime meaning, which may not always be the case for sharing a spec (which is more akin to sharing a JSON blob than a binary). Once again, reliability is a concern here.

Though if the meaning needs to be slightly different in a specific context, the source code format may not be as necessary. Depending on the meaning variance, and what meaning is trying to be replicated, perhaps sharing a prompt is more suitable. However, I would suspect that the prompt would need to be altered to suit that new meaning.

— 1/27/26

Thoughts on the Future of Libraries

What’s the point of libraries now that one can just generate them? The inital question I posed above comes from this article, but I’ve also watched others give their thoughts on the topic like Theo’s video.

This is a great question, and in fact I did just that last night for my new SQLiteVecData library, which provides interop for Structured Queries and SQLiteData with the sqlite-vec extension. That being said, I still shipped it as a library and put it publicly on the Swift Package Index.

That only begs the question of why I did this. After all, the library is also something you could generate yourself with just a few specs/plans in a short amount of time.

When we ask the question about the relevance of 3rd party libraries going forward, we have to consider a few things.

- What are we depending on?

- What are the costs of getting it wrong?

- What is the minimum knowledge threshold required to maintain it?

- Will I reuse it across different projects?

- etc.

These of course are all questions you would’ve asked yourself in the pre-agentic era, but it’s certainly now worth asking yourself these questions again from first principles.

From what I’ve found, simple libraries that merely save syntax are almost certainly things that you should generate yourself. This would include things like HTTP API clients, common UI components, things like react-hook-form, or even just any sort of basic wrapper functionallity.

For instance, in the Swift world there are many HTTP client libraries

that wrap URLSession, though 2 of the more significant

libraries are Alamofire and the OpenAPI Client Generator from Apple.

However, for all my projects I still just use

URLSession with very minimal generic abstractions on top

of it. In fact, in today’s world, I see even fewer benefits of using

things like Alamofire and the Open API generator directly. For the

former case, agents are trained on all of the common HTTP strategies

that Alamofire implements. In the latter case you could simply hand

the agent the API documentation, and it could probably generate the

client itself.

SQLiteVecData also falls into the thin wrapper category, which is why it was so easy to generate. Yet, the reason I published it is because I plan to reuse it in different projects, and it would be a waste of tokens for me to generate it again and again. So I suppose another benefit of 3rd libraries is that they could potentially reduce token consumption, even if they are a simple wrapper.

Though, one of the other questions people have of course is related to needing to coordinate with maintainers to resolve any bugs/missing features in the 3rd party library. Why should I have this communication overhead if I can just generate things myself?

For source-available libraries, you could always make your own fork depending on the license, and then modify the existing library using agents. In fact, this is the primary reason I still am publishing even simple wrapper libraries like SQLiteVecData. Even if someone wouldn’t install the package directly into their project, agents could almost certainly both fork and add/modify any behaviors in the library. It would also likely do that faster than generating your own solution from scratch, but in this case you still own the dependency.

Even if you don’t modify the library directly, and still opt to generate your own implementation, you can also use the libary’s source code as a way to guide the agent in your own internal generation through injecting it into the context. After all, whenever I would opt to write an internal implementation of a library in the pre-agentic world, I would still commonly look through the existing solution’s source code as a reference.

So wrapper libraries may not be useful to install and use directly, but their mere existence certainly can help when generating your own internal solution.

That brings us to more complex dependencies such as React, SQLiteData, GRDB, etc. In these cases, the library implements some sort of robust component that took significant amounts of engineering time (eg. UI reactivity for React, CloudKit sync engine for SQLiteData, Proper database connection/concurrency/transaction management for GRDB.) Generating these yourself will be a challenge, and is definitely a decision you should make conciously.

For these dependencies, I would still be inclined to use them directly. Either because the cost of an unreliable implementation is too high, or because the dependency provides a unique way of thinking for building parts of your system (eg. React’s component model).

Even then, when you need to make changes you can still easily fork and generate additional features. In fact, it’s never been easier to create and maintain internal forks of existing libraries.

I think this is fantastic. If someone decides to fork one of my libraries, and adapt it for their own purposes instead of installing it directly, then I treat forking as a bigger win for me. It shouldn’t just be a binary choice between installing and using directly, or generating from scratch. There’s certainly a middleground here, and not acknowledging it is a very limited outlook.

— 1/26/26

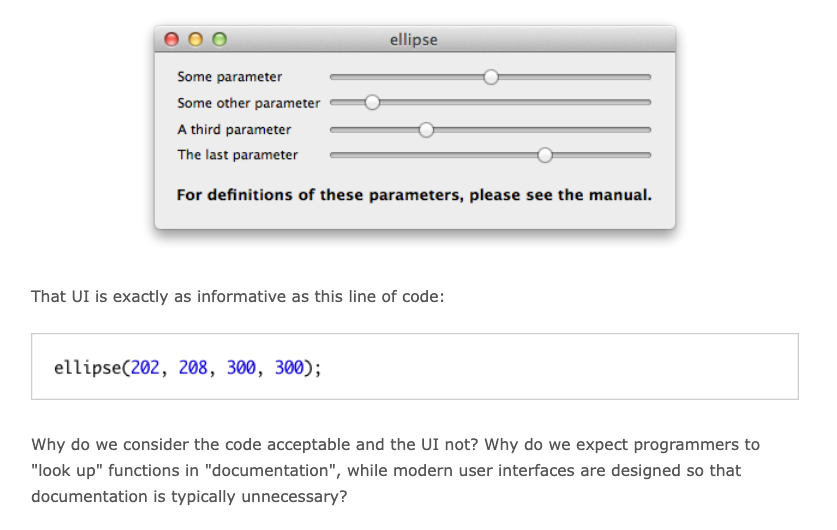

Communicators and Mediums

In the world, we often value one’s ability via their communication skills. That is, the ability to communicate is weighed heavily in one’s favor if they can do it. Likewise, not having strong innate communication skills acts against a person often in ways they don’t understand.

Let’s say I ask you to explain a complex topic to a 5 year old, like Albert Einstein wants you to. Your explanation will likely diverge to using visuals, and almost certainly not complicated text passages. In this case, that would be a good use of your communication skills.

However, if I forbid you from using visuals, what would happen then? Chances are, no matter how good of a communicator you are, you will struggle with your explanation. 5 year olds don’t have a sophisticated vocabulary or much understanding of complex ideas since their brains are still developing, so it’s less likely that text passages (which are incredibly abstract) will work.

I see this as a problem with common tools like Slack, Github, Zoom, Google Docs, Excalidraw, etc. today. If your team uses all of these tools, then the entire collective knowledge base held by your team is essentially fragmented, and the only way to make any sense of it is via good communication. Yet, even the best communicators accidentally leave our relevant context, or otherwise mistate things. In my experience, a lot of this is merely caused by simply forgetting to add those points, or assuming that the audience has that context. The latter can be an especially fatal mistake if the assumption is incorrect.

This is why I hold the general view that one’s ability to communicate is dependent both on their communication skills and the available mediums of communication they have. Someone who can draw well, but not talk, can draw a picture worth 10,000 words. Take away drawing as an available medium, and they can’t communicate all of a sudden.

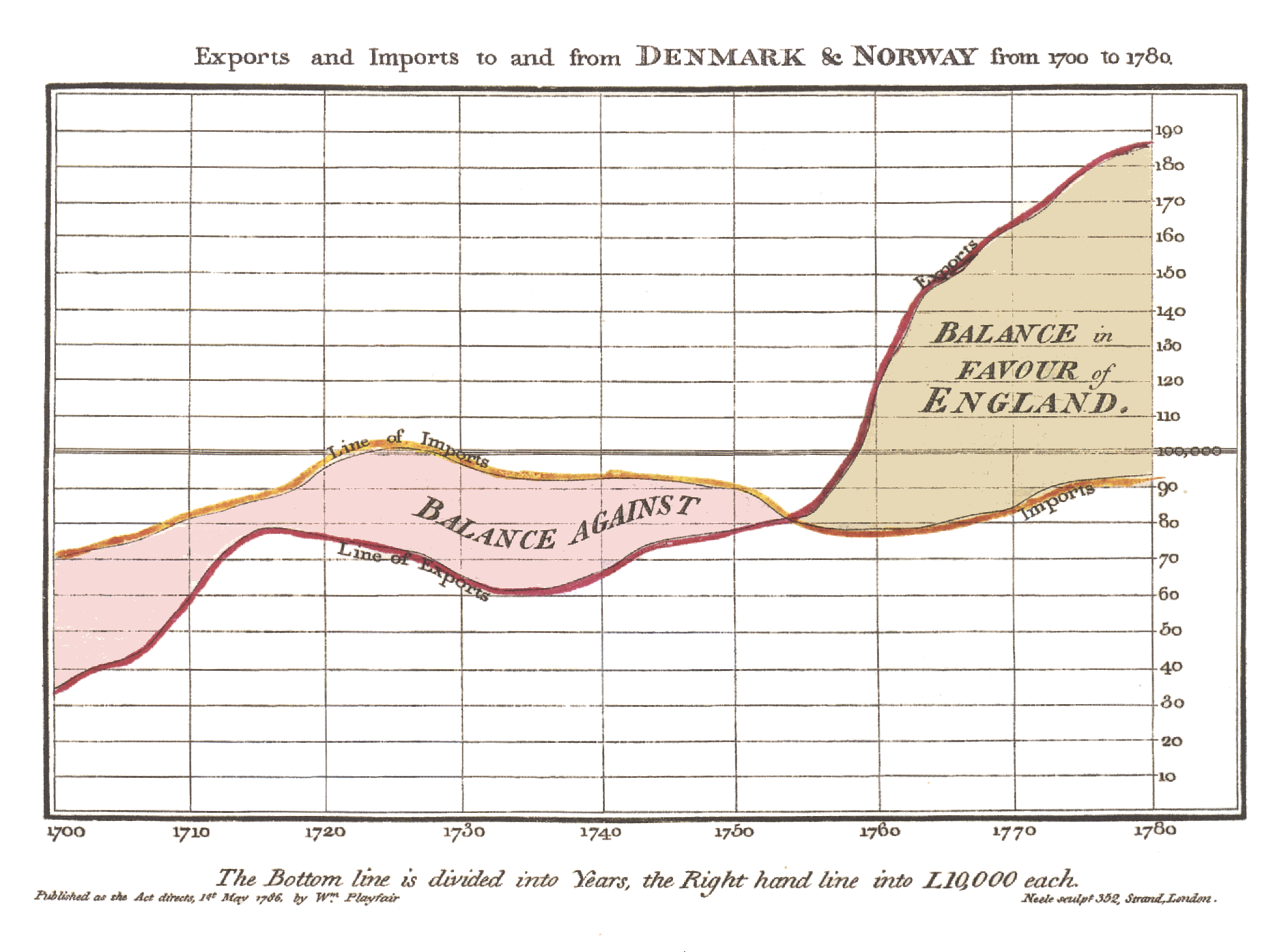

An interesting fact, we all seem to crave looking at graphs and charts

today, but did you ever consider how those things were invented? In

fact, in the nearly 200,000 year observable history of humanity, only

240 years ago in 1786 did William Playfair invent the modern chart in

his book The Commercial and Political Atlas.

Yes, that means that Newton, the invention of the modern state, the Scientific Revolution, and much more were invented without such a visual. Yet the key thing to understand here is that mediums like the chart enabled far more scientific discoveries in subsequent centuries.

Computing went through this kind of revolution in the 60s and 70s through the great research labs of the time (SRI, ARPA, Xerox, etc.), and gave rise to the GUI, internet, personal computing, and much more that we take for granted today. Though the key thing to understand was that those groups had a very different view of computing as do we today. Today, we’re obsessed with boosting productivity through automating work-related tasks instead of boosting collaboration through shared knowledge systems.

However, the thing to realize is how many ideas we’re missing because there is no UI for them. If your team uses Slack, Zoom, Github, etc., then you’ve fragmented correlated knowledge across a bunch of isolated apps. When 2 people are talking about a feature in Slack, is Slack inherently linking the relevant lines of code, analytics, crash reports, etc.? Or is it up to one of the those people to add the relevant context? What if the relevant information is completely external to the team? How does that get linked?

How many ideas are you simply not thinking of because you simply can’t see them through the UIs presented by the standard suite of tools? What if a different UI could get you to think of the right ideas?

In a world where everyone says its easier than ever to build your own tools, I would expect there to be some progress in the near future. Your internal recreations of Slack and Zoom into your team’s knowledge ecosystem can crash a few times per day, don’t need a fancy UI, and don’t need additional people to communicate with any third parties.

From a business competition standpoint, if you only use the standard tools of today, then you’re on the same playing field as everyone else. It’s now more possible than ever to change that no matter how many resources you have.

— 1/25/26

Performant Code and Agents

Of all kinds of code that I’ve tried to get agents to write, performant code is by far the hardest. It’s easy to get it to spit out code for a parser or for some cool canvas effects in a web application, however if you don’t know how those things behave with heavy workloads it’s going to be quite rough.

I’ve also seen it suggest false paths with respect to performance

optimizations as well. For instance, in Swift Stream Parsing, the

primary bottleneck is key path indirection in writing to a value on

every single new byte, and the amount of branching from byte-by-byte

parsing. This massively slows things down, and due to the specific

nature of the library is completely unavoidable. That’s why I don’t

recommend it as a replacement for JSONDecoder and

Codable, but rather for very specific scenarios such as

parsing structured output from an LLM.

Yet the LLM will still try to come up with proposed speedups, possibly for the sake of making one feel competent. (eg. It came up with an approach that would cache a stack of appended key paths instead of recreating the path from scratch on every new value detected. It turns out that didn’t help all that much because the stack is often obliterated and recreated when entering/exiting objects and arrays.)

Engineering knowledge is now more important than ever it seems, especially when dealing with a confident sounding LLM. Let’s not forget that.

— 1/22/26

Geoffrey Huntley Did Not Kill Software Development

If you’ve been like me and are trying to not be left behind™ , you may have heard of a recent development in which the Simpsons have virally taken over twitter. If you haven’t heard, and because you absolutely will be left behind™ otherwise, it’s called a Ralph loop. The idea is quite simple, is not tied to any plugin or tool, and consists of running an agent in a loop with a fresh context for each iteration. Often, if the agent seems to be doing well in this loop, you can leave it unsupervised to do its own thing.

However, if you’ve read any of Geoffrey Huntley’s posts, or watched some of his talks, you’ll find that he likes to directly point out that he, Geoffrey Huntley himself, has killed all of software development. So, now that modern software development is $10.42 an hour, how could he be wrong about this?

Let’s imagine an existing iterative development process in which developers are assigned tickets, and they complete them one at a time until the process is finished. Now, normally we’d like to think there are no roadblocks, but it turns out they happen all the time and intervention is needed. Some tickets get delayed, put on the backlog, or even scraped entirely for all sorts of various reasons.

In the case of Ralph Loops, Geoffrey Huntley himself states that you must step in and put your engineering hat on when one of these roadblocks are encountered. Then supervise the agent for a few more iterations before going back to DJ-ing.

So we have a live running process that we need to communicate with to get around a road block in its current path. There seems to be a required collaboration between machine and human to make this communication possible. Therefore, there has to be an interface somewhere to do this. The agent is perpetually running in a loop, autonomously or not, so any updates to the process that we make will therefore be received and implemented pretty quickly.

In other words, this is a form of live programming! It’s a concept that was widely important in the 70s at PARC! Smalltalk was such a good example of a live programming system, and any change to the code would be recompiled into the system incredibly fast. So fast, that the change itself would be visible in real time unlike most programs today where you would have to recompile and run the entire binary from scratch.

Once we start thinking about programming as moving around living and real things, a lot of powerful ideas are unlocked. For instance, we see how programming becomes more about dynamic processes rather than manipulating static bits inside data structures. We’ll also have to take parallels to the physical world in which beings in society can be considered running programs, and how we design infrastructure for those programs.

However, I want to make clear that a loop is just one kind of process, and that thinking all of software development in terms of mere loops is a very limited and short-sighted idea. This isn’t to say that the Ralph Loop has no merit, but rather that on its own it’s not even close to the style of thinking and operating that is actually needed here. I think even Geoffrey would agree with that statement by the way.

Us humans are also theoretical biological ralph loops that are always running, but we don’t have to repeat very defined processes thanks to free will. We generally have to make decisions based on information, and we also very much like to say the words “if” and “when”.

How will one orchestrate this for continuously live running agents? Well if how we handle the physical world tells us anything, we’ll need lots of processes in place. Those processes will further have to be compatible with dynamic behavior. Additional processes will also be needed to create new processed in a meta-language like fashion.

So there will be quite a lot of software development in fact, because inevitably there will be so many edge cases for Ralph loops that we’ll need processes to handle them. In other words, at this moment is our chance to create a new programming environment (not just textual language) that prioritizes processes and building systems rather than just enhancing our ability to write text faster.

This last thing is absolutely incredibly important, and messing it up can have serious consequences. Anyone responsible for building such a system at the bear minimum should take time to understand many of the ideas from the pioneers of computing, and absolutely not proceed with anything until this paper has been fully read and understood. The last time someone attempted this without reading that paper, we got the web and a lot of regret from its creator.

I would rather that not happen this time.

— 1/21/26

Most Systems are Safety Critical

This might sound quite ridiculous to say, but I think of TikTok as a safety critical system. Yes, in the same sense as medical devices, automobiles, etc.

With that latter kind of system, it’s quite easy to conclude that “bug in software -> potential death”.

For TikTok, I would say that “bug in user interface -> potential death”, where the user interface is naturally a subset of software. TikTok’s biggest user interface bug is keeping you endlessly trapped in a false perception of reality. This has no doubt led to deaths and widespread pyschological issues across society.

Though even a simple bug in the code can cause issues. If TikTok was taken offline from such a bug, you may think of it as just a simple inconvenience. However, their user interface bug has created quite a psychological dependence on the platform for younger generations, and taking away an addictive substance abruptly usually isn’t a good cure. Also, for better or for worse, TikTok is an archive of collective knowledge that may need to be accessed for non-trivial purposes, so workflows that depend on that archive (eg. Court) may be disrupted.

If we look at the overall landscape of damage, would we say that automobile accidents, or mental health issues are bigger?

Of course, both are bad, but inuitively we more clearly see the consequences of automobile accidents over mental health issues. In fact, many say that mental health isn’t a real problem!

Automobile accidents are also very easy to measure compared to the effects of mental health issues. To measure the latter, you need to use more science, and often infer conclusions based on a number of downstream indirect measurements (eg. An oversimplification: Poor mental health -> bad performance at job -> company loses money).

Unfortunately, most people think of science as a jumble of facts instead of as a way of thinking, and will use facts discovered by scientific thinking when it’s convenient for them, which is often when trying to win an argument. They’ll claim that their ideology “follows the science”, but in truth they are just using rhetoric, which is exactly the opposite of scientific thinking.

Jumbles of facts are also not a replacement for systems understanding. If we don’t universally learn the latter as a society, we’ll never acknowledge many of the real issues caused by our man-made systems. You may believe that universal learning is practically impossible, but we’ve already achieved it with literacy. Nearly every citizen on the US can read at least a little bit thanks to public education, which is why TikTok even works as a business in the first place.

Regardless, I’m going to take a wild guess and assume that most software engineering at TikTok is the typical kind of gluing things together, often between tightly coupled distributed services (Though TikTok is at the scale where microservices make sense), possibly skipping out on tests for time’s sake, and writing “good enough” code to reach arbitrary deadlines.

Does TikTok need assembly level code verification like other safety critical systems? Probably not. However, its user interface surely needs to go through real clinical trials, and its infrastructure also needs to be heavily audited to prevent outages from blocking data access entirely.

— 1/17/26

LLMs and Creatives

To add on to my never ending writings about LLMs and systems design, we’ll now address actual creative work. To define creative work, I’ll consider it as any body of work that inherently produces novelty. To this extent, art, writing, music, etc. are all included.

As I’ve stated previously, the point of creation isn’t to have a model generate a bunch of variants, and then have a human pick the best one. Whilst a model can generate creative work far faster than a human can create it, at the end of the day LLMs are really just incredible statistical pattern matchers based on a limited context window.

Good creative work often doesn’t follow statistics, and is rather an output of intuition. The intuition is required for novelty, because statistics by its own nature must use what already exists.

My primary role in the economy is to build software, and to those ends the code is required to be written in a certain way to produce a quality system. Robust software often requires measuring statistics in some form, whether that’s through tests, infrastructure costs, performance benchmarks, analytics, or whatever else. Improving these things is often an optimization problem, which is a perfect problem shape for pattern detection algorithms like LLMs. Generally, this doesn’t take the meaningful work out of creating software, because the actual hard creative work typically happens in one’s head long before that sit at their desk.

Similarly, the role of airline pilots is to transport passengers or cargo from one destination to another. For each destination and the environment around it, there is an optimal flight path that one can take. This is an optimization problem for which autopilot is the current solution.

However, art, music, and writing are absolutely not optimization problems, and trying to make them optimization problems is an absolutely terrible idea. The point of pure creative output is to express ideas, often in an open-ended form, and to communicate to other humans. Without that, we lose out on so much, including learning novelty required to design more robust systems.

Does that mean LLMs are an entirely bad idea in creative fields? No, but they need to be working to enhance creative output rather than taking away the process entirely. The solution to this clearly lies with the design of LLM-based tools.

LLMs have an inherently large corpus of knowledge, and are more available than other colleagues to review existing work for example. As such, they can offer realtime feedback by picking up on queues from watching humans create. In pair programming for instance, the partner watching can pick up and learn from just seeing the driving partner type code without any additional communication.

Right now, LLMs almost entirely accept specifically crafted textual/file-based prompts as inputs. Often, these prompts are entered into a tiny text box on a window somewhere off to the side of the actual creative work. Therefore, by nature, one has to stop doing any sort of creative work in order to engage with the LLM. This in turn, takes one out of the creative flow, and as a result is likely to produce a worse overall outcome.

In other words, we need more forms of inputs! If you keep the input mechanism to entering text and dragging files into a tiny text box, almost certainly people will be upset that the fun is being taken out of the creative work.

— 1/17/26

Skill Atrophy

One of the biggest counter arguments I’ve seen to agentic coding is the idea that your skills will atrophy if you start adopting agents to write all the code. Firstly, while the agents are now good enough to write most code in many cases, they certainly aren’t good enough to write all code yet. So at least on that front, your handwriting skills will still be necessary for quite some time.

However, the main point that I want to make here is that you can only upskill so much by repeatedly manually writing simple UI components, network calls, database queries, caching, or simple business logic. That is, writing the code for these things isn’t typically all that hard, but rather more time consuming than anything else. The hard part is generally how all of those components are orchestrated in the larger system, and how they are isolated from one another. That’s why mobile developers love talking about app architecture and design patterns.

For IO bound systems, you can generally write the code as verbose as you want, as decoupled as you want, and favor readability over performance. At the end of the day, you’ll likely still have fine performance at the individual lines of code level regardless of the style you choose. This is because the actual application performance optimizations generally come from designing a better higher level architecture with less latency/throughput/better resource utilization/etc. This architecture largely exists outside of the code.

Now of course, for compute bound systems the actual code matters a lot

more. You can’t just add 15 levels of indirection, or use convenience

algorithms (eg. .map in JavaScript) if you need top-notch

performance. Even choosing between contiguous vs non-contiguous memory

based data structures can have a massive impact on performance in such

cases.

Thirdly, there are frameworks that often require stretching a language to its limits to provide a more convenient API to end-users. Often times, the interface needs to be carefully crafted, and in statically typed languages, the way you define types is akin to a work of genuine art. I still remember when my colleague wrote an internal TRPC clone, and the typescript types were an absolutely beautiful work of art to admire.

Generally speaking, I think skill increases for most programmers come from either investing in better architecture, writing performance intensive code, or writing framework code. Even just spending a weekend writing a fast JSON parser by hand will probably improve your skills a lot more than writing 300 HTTP API calls by hand over the next few months.

Right now, I think those things are what agents are lacking in, because both require lots of precision to get right. I imagine agents will improve at both those things in the foreseeable future, but the improvements will be slower than the ability to churn out more IO based systems. In the real world, it just seems that more IO bound systems are directly making money than compute bound systems, so obviously the model improvements will follow that direction.

In the meantime, if you occasionally opt to write performance intensive and code that requires precision by hand, then your skills will probably continue to increase despite using agents for everything else. At the end of the day, novelty in writing code will yield more improvements.

— 1/15/26

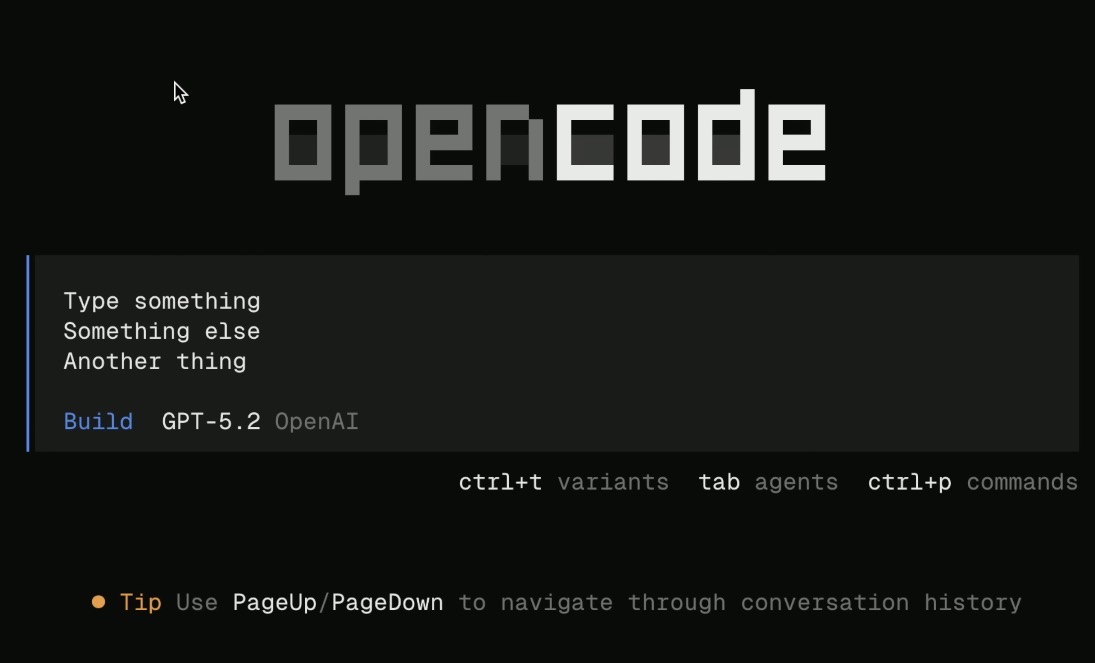

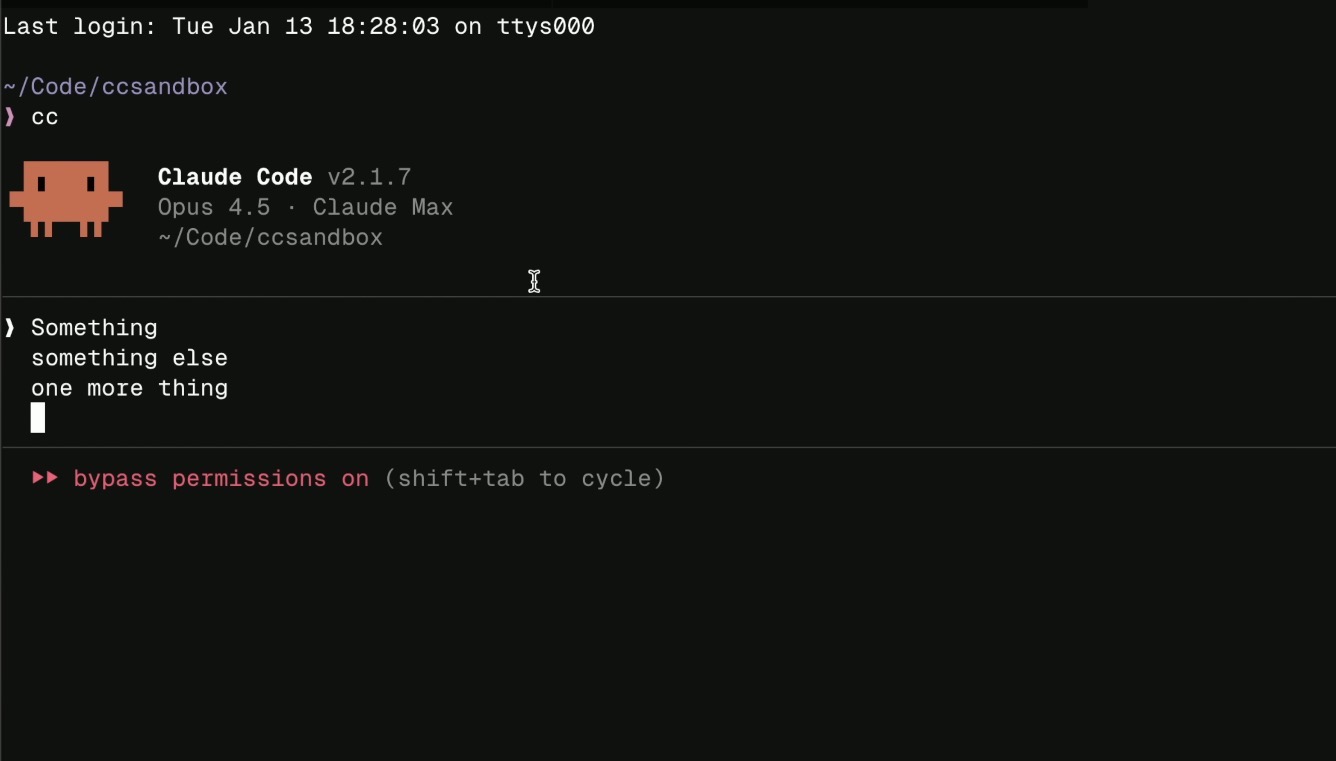

The Agent is Dark

How much of your system can you see from this?

Or this?

I don’t see anything but a black background, a text box, and a weird animal looking thing. We have a long to go…

— 1/15/26 (2:13 AM)

Native vs React Native in 2026

Ah yes, the classic debate.

For context, I’ve worked professionally in both Swift on the iOS and watchOS side (alongside many open source libraries that I maintain), and React Native with Expo.

In the past, my opinions on the matter were quite nuanced, but were something like this.

- Native code generally has less dependencies, and platform feature are available as soon as Apple releases them.

- It’s easier to do platform UI and extensions (eg. Widgets) in native.

-

Persistence and storage are definitely better in Native.

-

expo-sqliteis quite limited compared to GRDB and SQLiteData. - React Native libraries tend to be geared towards simple use cases.

-

-

Native code is easier to get right and make performant given that

it’s generally compiled to machine code and not interpreted.

- Both Native and React Native can build great apps, but generally the best apps I’ve used tend to be native.

- React Native has the advantage of speed of shipping.

-

React Native is great for unified UI across both iOS and Android.

- Skia is also quite fine for graphics.

-

API back deployment is easier in React Native.

- It’s quite easy to build a React Native app that supports many previous OS versions, whereas it’s annoying to support more than the past 3 in native Swift apps.